Don't Fail Greta

Don't Fail Greta

|

| Greta speaking at the UN climate action summit. Source: Yahoo |

Let's not fail her.

One common response I have heard over the years, one way of deflecting the issue is that a person can't affect it. That idea is wrong. We can affect it. The most straightforward way of affecting this - and one that many of the same people didn't do - is that we live in a democracy. Vote for policies that

will reduce the emission of greenhouse gases.

Over the past period, I've taken a look at how to reduce my own footprint. I would like to share the information with you.

What can you do?

But beyond voting, what can you do? How can you reduce your own impact? Can we reduce our own impact by at least 50%?

Well, to take a look at that the very first thing we should ask ourselves is what is our own impact. This is a question I've asked myself over the last few weeks, and I think it is good for all of us to be aware of it.

Because it varies for everyone, we should decide what we are going to be talking about. It's easiest to relate to my own situation, which would be that of a one-person household and driving to work. I'm at the end of my twenties. That is the situation we'll base the numbers on.

Let's take a look at the larger factors:

- Commute by car (around 12000 km yearly)

- Food and drinks

- Electricity and gas usage

- Consumerism

- Netflix! (and similar)

The individual CO2 factors: Travel by car

Let's take those factors and calculate the emissions (CO2 equivalent) that they generate. By realising what we contribute, we can see how we can reduce that contribution.

Let's start with the car. First, we need to determine the kind of car. Because we will use an average 12000 km travelled yearly, the petrol version will be the financial decision most people take. However, cars are so different that we need to consider a few situations:

The best decision? Move closer to work. Don't drive as much. I'll be moving closer to work next year, which will greatly reduce the distance I travel by car.

Let's start with the car. First, we need to determine the kind of car. Because we will use an average 12000 km travelled yearly, the petrol version will be the financial decision most people take. However, cars are so different that we need to consider a few situations:

- A simple car to drive to work with. One popular example is the Ford Ka (second generation), whose petrol version generates 119 g/km CO2. This would generate 1.428 metric tonnes of CO2.

- A slightly larger 5 doors, the Volkswagen Polo. The emissions are at least 138 g/km CO2, which generates 1.656 metric tonnes of CO2.

- A slightly older car, such as the Ford Focus (first generation). At 158 g/km CO2, it generates 1.896 metric tonnes of CO2.

Overall, a comfortable estimate would be 1.5 metric tonnes of CO2 due to travel by car. Car choice really matters as we see above. The cars above are all reasonably common, but not overly large.

Switching to a 100 g/km CO2 car, like a Suzuki Alto or a Toyota Prius (which are not in the same price category at all) allows you reduce your footprint to 1.2 metric tonnes, a decrease of 0.3 metric tonnes.

However, there's another trick. Eco-driving, the "new driving" allows you to save as much as 30% on both fuel (your wallet) and CO2 (the climate) (source 1, source 2, Wiki).

I monitor my fuel usage when I'm driving, and noticed that I could use 20% less fuel on my commute. That should directly translate to 20% less CO2 exhaust!

If we take both into account, the contribution from travel by car goes down to 0.96 metric tonnes, a reduction of 0.5 metric tonnes.

As a last point to discuss, we have the cost of manufacturing. A CO2 emission of manufacturing a car can be anywhere from 5 to 35 metric tonnes of CO2. As a result, we need to consider this cost. Most cars will be able to drive anywhere from 200 000 to 400 000 km in its lifetime. As we've seen, a greener car (100 g/km CO2) would produce around 20 to 40 metric tonnes of CO2 emissions in that lifetime. Does that measure up against the amount you'll be driving with it?

The answer depends a lot on how much you'll drive it. Consider a choice between the Ford focus, at 1.896 metric tonnes of CO2 and a small car (Citroen C1) that comes in at 10 metric tonnes of manufacturing cost. It will take about 14 years (14 x 0.7 = 9.8) for that cost to be returned. However, at that point, the car is not at the end of its lifetime yet (14 * 12 000= 148 000)! The same calculation, however, for the Land Rover Discovery would be very different. At 35 metric tonnes, it would take 50 years to return that manufacturing cost - which is more than its lifetime! And that was assuming it has 100 g/km CO2 emission - it doesn't.

My personal decision here is to do all of the above. I'm replacing my car with a lower emission profile (Toyota Yaris Hybrid at 80 g /km), I'm already using eco-driving and the car I'm buying is a second-hand (manufactured 2012 or 2013). That would feature at 0.768 metric tonnes, which is a 50% difference even when compared to the lowest (Ford Ka) situation.

As a last point to discuss, we have the cost of manufacturing. A CO2 emission of manufacturing a car can be anywhere from 5 to 35 metric tonnes of CO2. As a result, we need to consider this cost. Most cars will be able to drive anywhere from 200 000 to 400 000 km in its lifetime. As we've seen, a greener car (100 g/km CO2) would produce around 20 to 40 metric tonnes of CO2 emissions in that lifetime. Does that measure up against the amount you'll be driving with it?

The answer depends a lot on how much you'll drive it. Consider a choice between the Ford focus, at 1.896 metric tonnes of CO2 and a small car (Citroen C1) that comes in at 10 metric tonnes of manufacturing cost. It will take about 14 years (14 x 0.7 = 9.8) for that cost to be returned. However, at that point, the car is not at the end of its lifetime yet (14 * 12 000= 148 000)! The same calculation, however, for the Land Rover Discovery would be very different. At 35 metric tonnes, it would take 50 years to return that manufacturing cost - which is more than its lifetime! And that was assuming it has 100 g/km CO2 emission - it doesn't.

My personal decision here is to do all of the above. I'm replacing my car with a lower emission profile (Toyota Yaris Hybrid at 80 g /km), I'm already using eco-driving and the car I'm buying is a second-hand (manufactured 2012 or 2013). That would feature at 0.768 metric tonnes, which is a 50% difference even when compared to the lowest (Ford Ka) situation.

The best decision? Move closer to work. Don't drive as much. I'll be moving closer to work next year, which will greatly reduce the distance I travel by car.

Individual CO2 factors: Food

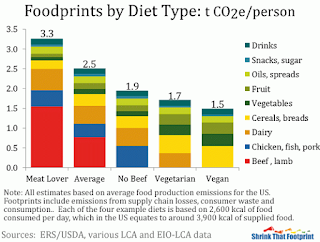

The next factor, food and drinks, is a lot harder to consider. Diet choices matter ( a lot ). Let's take a look at a graph, but remember we can't take a singular source to be truth in this matter.

|

| Diet carbon footprints. |

- Eating pork 1-2 times a week (0.14 metric tonnes), and beef 4-5 times a week (1.6 metric tonnes) for a total of 1.74 metric tonnes.

- Eating pork 4-5 times a week (0.375 metric tonnes), and beef 1-2 times a week ( 0.6 metric tonnes) for a total of 0.9375 metric tonnes.

What about drinks? Let's make a few lists. Because I can't honestly say how much a person drinks, I will just write down several scenarios again:

That saves you 0.8 metric tonnes. Food choice can make a big impact.Individual CO2 factors: Drinks

- 1 Litre of coca-cola a day keeps the doctor away (but not the dentist).

- A litre of cola comes in at around 200-250 g (diet is less).

- A litre a day would be 365.25L a year, or 73 - 91 kg CO2 per year.

- 2 Litres of water per day (recommended dose)

- A litre of (tap) water is approximately 1g CO2

- A litre of (tap) water a day would be 0.365 kg CO2 per year. It's not much.

- A pint of beer a day.

- A pint of beer represents 300 - 900 g CO2.

- A pint a day would represent 109.575 - 328.725 kg CO2.

- A bottle of wine every 4 days:

- A bottle of wine would feature anywhere from 300 to 4500 g CO2. Let's take the lower one, 300 g CO2. (Source: Figure 3)

- This would lead to 300 / 4 = 75 g CO2 daily, for a total of 27.394 kg CO2. Keep in mind that the whole lifecycle of the wine can contribute to that number being as much as 15x bigger.

- 1 Litre of apple juice a day.

- A litre of apple juice would contribute 500g CO2.

- A litre a day would contribute 182 kg CO2 per year.

|

| Drinks picture from Wikipedia |

Honestly, I expected the beer to do worse and apple juice to do better. Guess we should be drinking tap water more often! (if viable in your area).

Overall, the influence of drinks seem to be a far smaller contributing factor than food is!

Individual factors: Electricity and gas usage

So, let's start with finding the average use for our single-person household. I know where I can find the numbers for the Netherlands:

- 1800 kWh yearly

- 650 cubic metres of gas yearly

Electricity is easy to convert. A single kWh would contribute an average of 447 g CO2 in the EU, so the yearly contribution of electricity for a single person household is 0.8 metric tonnes of CO2 due to electricity usage.

Natural gas was harder to determine. For each million Btu of energy from natural gas, 117 pounds of CO2 are emitted. Which means that for 1 GJ, around 53 kg of CO2 is emitted.

Finally, 650 cubic metres converts to 24 GJ ( 37 million joules per cubic metre). That's 1.272 metric tonnes of CO2 due to gas usage.

This, in turn, means that using less gas (i.e. less hot water, less heating) allows you to make a large impact.

Individual factors: Consumerism

Oh no, this communist leftist is going to tell us to stop buying new stuff! Well, not exactly. I'm just going to point out two things. I'll be using the iPhone as an example, but this will ring true for any gadget or appliance you buy.

First off, an older generation iPhone is going to be priced similarly as a secondhand to a newer generation budget phone. They should have similar performance. Consider the second hand, maybe?

An iPhone 6 has a lifetime carbon footprint of about 110 kg of CO2. Consider if this is worth it for a shiny new toy. Regardless, make it last. Having phones circulate on the second-hand market is good for the environment!

Again, phones were just an example. Some other examples we could consider:

- TV screens

- PC monitors

- Nintendo Switches

- Tablet devices

- Laptops

- Computer Parts

- Headsets

- Bicycles

Secondly, consider looking into the contribution of that new toy. Was it taken into account for the manufacturing process? How will it hold up - longer lifetimes are better? Does the manufacturer have a green profile?

I'm not a communist. I rather like capitalism, but monetary value is not the only value we should focus on. I honestly believe that we should focus also on values such as sustainability. It's worth spending money on (if you can spare it, that is).

Individual Factors: Netflix!

Netflix is just an example, but most of us depend on some services for our daily media fix. I can't put a CO2 value on Netflix, Youtube, WhatsApp or Instagram. I can only point out that there is a hidden CO2 cost for digital products as well.

To give you an example, video content is apparently generating as much CO2 as Spain does.

When considering signing up for a new service (I'm looking at you, Disney) it is also sensible to consider whether or not that company is open and clear about its decisions on sustainability. To give you an example, here's Google's sustainability page. In the interest of fairness, Here's Apple.

Conclusion

In this post, we took a look at the contributing factors to our own carbon footprints. My personal surprise was the contribution of a meat-first diet, which is larger than the contribution of a car.

We considered gains we can make, and identify simple ways to reduce your personal footprint by metric tonnes yearly. That's impressive.

If the western world alone does that, with its population of around 2 billion people, we can cut our footprint by a few metric gigatonnes. I know, it's only a few per cent of our total output. But we've also discussed placing an economic value on sustainability and voting for sustainability.

We can contribute. How dare we not?